📅 Posted 2021-10-18

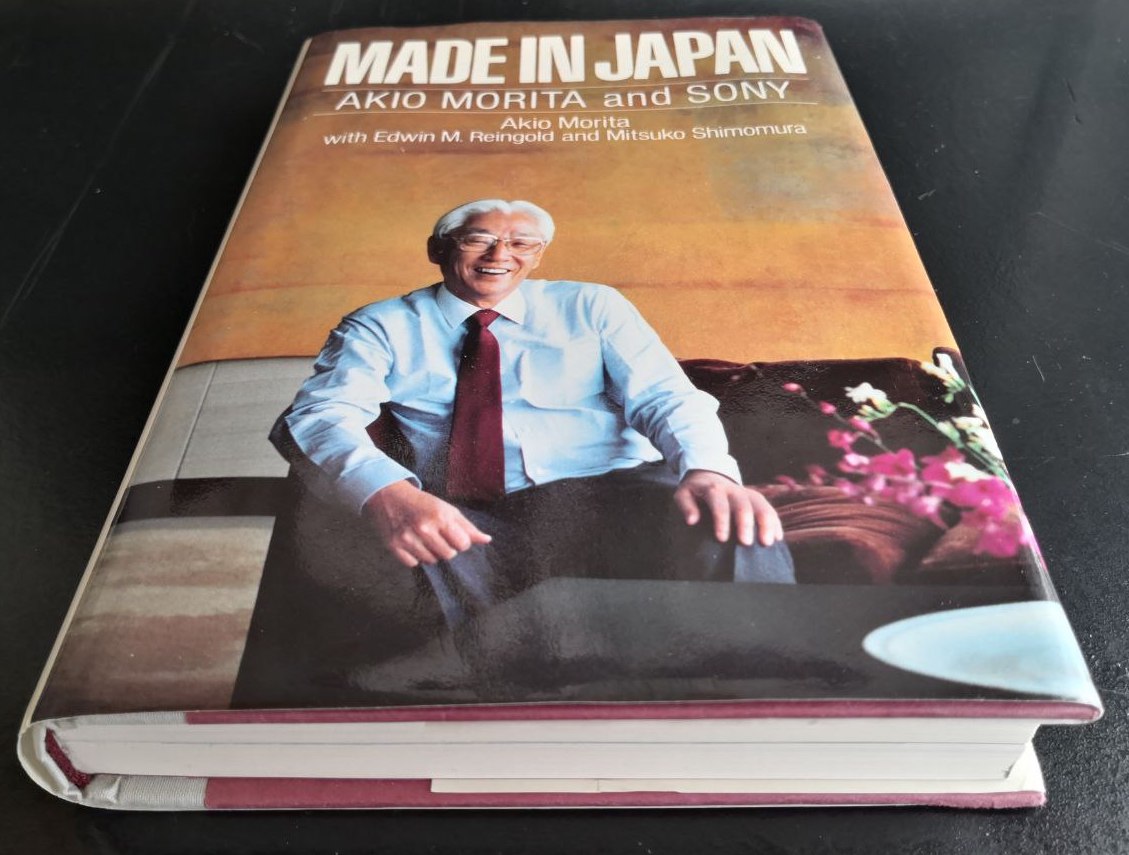

Lately I’ve been reading Made in Japan: Akio Morita and Sony which is the autobiography of Akio Morita, co-founder and former chairman of Sony Corporation. It was originally written in Japanese of course, but I’m reading the English version 😊. What attracted me to this book was Morita’s famous quote about the Sony Walkman:

“Nobody openly laughed at me… Everybody gave me a hard time. It seemed as though nobody liked the idea… I do not believe that any amount of market research could have told us that the Sony Walkman would be successul.”

Sadly my copy of the book arrived with a scuffed corner (I bought it used on eBay, which was the best value at the time) as it was really poorly packed, but I did get my money back at least. However, I hate ruining things! I’d rather keep the book in as good condition as possible. No dog ears here! I guess I could have opted for an ebook version but I kinda like having the real hardcopy.

“Sony” was started in 1946 as an electronics shop by Masaru Ibuka with 8 employees, just as Japan was starting to rebuild itself after World War II. The company name Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation or TTK) was quickly established when Akio Morita joined Masaru Ibuka that same year. It wasn’t until 1958 until the company changed their name to Sony, which sounded a bit like “sonus” (Latin for noise or sound) as well as being a word unused around the world. There’s other theories too but they aren’t that important right now! Sony was the first company to list on an American stock exchange - the NYSE, which was a big deal for the company at the time.

What made me really get into the book, however, was the words of wisdom on leadership as well as the history of how the company came to be and grew into a dominant force in consumer electronics up to the 80’s.

Coming to today’s post, Chapter 4 “On Management (It’s all in the family)” really caught my attention and I figured I’d capture a few thoughts about this section as it was most relevant to my situation in my career.

One thing to note

Keep in mind the book was written in 1986, before Morita passed away (he died in 1999) and also before the “lost decades” of Japan’s stagnation from 1991 to 2003. So it can hardly be a testament to Sony today however does contain some fascinating ideas which can be applied to a modern world.

I’ve never worked for Sony, so this is purely an analysis of Morita’s wisdom and can’t be taken as any representation of the company today.

Also, Morita calls it “management” when he’s really talking about a blend of both “management” and “leadership”, which are differing yet complementary skills. But I think this could be due to 1980’s thinking, or translation from Japanese, or both.

And with that, onwards

The interesting thing about Sony to me - apart from my strictly fanboy obsession with the MiniDisc - is that they’re predominantly a product company with a strong presence in the consumer electronics field but also having a role to play in other segments such as video gaming, music, movies and travel.

I can see a lot of parallels between Sony and how a lot of government agencies want to operate in this ‘product’ perspective: how to research, design, develop, launch, support, expand, improve and retire products. These organisations are ultimately very different, particularly around their core funding difference between a publicly-funded government agency and a publicly-listed company.

The proceeding chapters 1~3 are still worth a read and set the scene about how Japan rose out of WW2 and how Sony started, and that’s of course a very important part of the story too.

It’s pretty obvious from a subtitle “It’s all in the family” that Morita talks a lot about running a company like a large family. Morita goes to great lengths to describe the cultural differences between Japan and America, but the standout fact for me was that People in Japan, during the time of growth for Sony, would join companies after graduating and stay there until retirement. That seems so different to how people in the West seem to be constantly on the move, jumping from role to role in order to step up the ladder or to engineer a payrise.

In the book, there is a strong emphasis on creating a healthy relationship between managers and their employees, which would entail a lot of harmonising as I can imagine. Morita says that success for companies comes from a shared sense of fate amongst managers and employees. I’ve heard he was a great “harmoniser” and it definitely comes across in his upbeat, optimistic and open writing style.

It’s important to be bold and daring (even if it is risky at times) but the future of the business is in the hands of the people that you hire. This trickles down to the youngest recruit on the staff. Morita says the fate of the business is in the hands of the youngest member on the payroll!

Graduates

Morita would personally address and meet all of the new graduates as they come into the Sony corporation. Two things stood out to me in how he imparts his wisdom on the new recruits:

“You should understand the difference between the school and a company. When you go to school, you pay tuition to the school, but now this company is paying tuition to you, and while you are learning your job you are a burden and a load on the company.”

and…

“If you do well on an exam and score 100%, that is fine, but if you don’t write anything at all on your examination paper, you get a zero. In the world of business, you face an examination each day, and you can gain not one hundred points but thousands of points, or only fifty points. But in business, if you make a mistake you do not get a simple zero. If you make a mistake, it is always minus something and there is no limit to how far down you can go, so this could be a danger to the company.”

I think this transition from a student to an employee was also something that was quite an impactful change for me too: going from having to turn up to class and hand in assignments for 11 hours a week (seems expensive given the uni fees and the lack of actual class time, looking back…) is totally different from having to turn up 5 days a week and focus on my work. They don’t really prepare you for “what really matters” in business. There is much less chance and opportunity for real assessment and genuine feedback in the business world.

About unions

Morita also talks a bit about labour unions. People who are strong in leadership may become a union leader. These kinds of people are actually very interesting for companies because management is always looking for people with persuasive qualities who can make others want to cooperate with them. He remarks it’s important to overlook the lack of education credentials if people possess other key qualities that make them ideal leaders.

It is quite clear from reading the book that Morita is not fearful of unions: far from it in fact. At the time of writing, there were 2 active unions which would have little impact when Morita compared the overall number of lost hours due to union activity in America, UK and Japan. He recalls one time of “outsmarting” the unions when industrial action could have derailed key celebrations for Sony by secretly changing the location to avoid protesters. Cheeky.

Always strive for good employee relations

This seems a little obvious but the vibe is:

“The business does not start out with the entrepreneur organising his company using the worker as a tool. He starts a company and he hires personnel to realise his idea, but once he hires employees he must regard them as colleagues or helpers, not as tools for making profits.”

He goes on…

“The investor and the employee are in the same position, but sometimes the employee is more important, because he will be there a long time whereas an investor will often get in and out on a whim in order to make a profit.”

(Side note: it does annoy me that the default is to refer to people as a “he”, which seems rather antiquated these days. I will forgive the book since it was published in 1986)

I know in the case of government departments and agencies, they don’t really have traditional investors (all Australians could be seen as investors, who have provided with the means to operate each government organisation) but I think embracing a sense of mutual respect across the whole organisation will support the organisation being the property of all employees and not just a few people in the top executive tier.

Mobility

It’s interesting that at this point in time in Japan- it was normal for people to stick with one company for decades (even their entire working life), and thus changing jobs would be quite unusual. Even changing jobs within one company was a big deal and wasn’t always encouraged.

Instead of being able to change to another job, Morita brought in the ability of employee mobility within Sony. The ability to move people from one role to another within an organisation has many benefits which were described in the book.

Some of the finer mechanics of the Sony mobility system include:

- All engineers are assigned to the production line to really understand how production works - this has challenges for people who join and think being an engineer means production is somehow “beneath” them!

- From direct engagement with employees, Morita would gain key insights from more social (and thus comfortable) situations such as dinners or organised social events

- Through analysing data, it was found that a lot of employees were using the mobility system all reported to the same manager, which enabled the company to manage the performance of a manager who was not working well with their employees

- It’s normal for employees to want to move but a mass movement could be an indication of another underlying problem

- Mobility opportunities are advertised internally

- Employees are encouraged to move to related or new work at least every 2 years

- Sometimes people apply for lower ranked jobs just because they really need a job, but with mobility, talents can be recognised and people can move into roles which inspire more performance from an employee

Morita remarks that this concept of mobility is not typical of Japanese companies but I think might be more common in Western companies, although not nearly used as much as I would like to see. The Japanese system seemed to be largely based on historical performance and even school/university scores, which seems really disappointing to lean on given it’s in the past and would be ineffective at measuring employee performance. So glad Sony broke this model!

Further reading on Morita’s mobility system is explored in his book Gakureki Muyō Ron (Never Mind School Records) which I couldn’t find a good English translation for at this time.

Free discussion

Sony did of course start with very humble roots: a couple of people in a bombed out building. So it’s easy to forget the giant corporation had start-up roots! One of the easy things to do initially was to discuss issues as a small company: you could fit all employees in a room! This would make free discussion really easy but this was a way of talking about problems that Morita brought forward as the company grew and grew into what we know it as today. I don’t know what Sony is like now - I’ve never worked there - but in 1986 it was still felt like there was the ability to discuss issues openly.

Japanese companies equate cooperation or consensus as the elimination of individuality. No individual is bucking the thread, so we have consensus. I find this would be really challenging for me and it was heartwarming to read that the Sony spirit was to bring ideas that challenge out in the open. I don’t see how we can shift to a place of improvement and innovation without taking a few risks and talking about new ideas broadly.

The role of the manager in a team is to facilitate the generation and sharing of ideas in harmony.

I hear the word ‘harmony’ a lot and sometimes it’s tricky to pick the option which harmonises teams the most even though the outcome might be technically ‘worse’ or deliver ‘worse’ performance. But when is it worth picking a better technical option that lots of teams hate?

Free discussion could also create space for debate and argument. To this, Morita supports healthy discussions and notes that if he had a clash with someone (as he did on occasion with board member Michiji Tajima), it was a good sign that both people are required by the company. If you agree on everything, then Morita notes the company doesn’t have room for both people because you would have “exactly the same ideas on all subjects”.

But perhaps it’s a question of scale? Sure, having multiple people “at the top” with identical ideas, drivers and vision is one thing, but sometimes you need lots of people with very similar views on topics so that leadership can be scaled across many teams. You can’t be everywhere at once!

Morita goes on to say that having people disagree can help de-risk the company by making less mistakes and to cross-check ideas. I like this to a degree: I like bouncing ideas off people who are likely to see the downsides over the positives, but it can be very tiring when you just want to see your vision through if you’re always met with resistance. Of course, the nay-sayers are usually right! So usually it’s wisdom that comes with experience, you just need to know how best to use it.

Who gets to think?

In Morita’s mind, the short answer is ’everyone’.

“A company will get nowhere if all of the thinking is left to management… and for the lower-level employees their contribution must be more than just manual labour.”

This is interesting because it’s the people who are at the coal face who understand the issues that they have to deal with on a daily basis. So it makes sense to canvas issues and suggestions for improvement from everyone, not just from management.

I do like how there is fostering of ideas and creative thinking at all levels and it was described as a genuine activity not just simply an exercise to appease the employees.

“A manager should not try to cram preconceived ideas into [employees] because it may smother their originality before it gets a chance to bloom.”

This resonates a lot for me as a manager of a team of architects as I really think architecture is quite a creative pursuit and I don’t want to seed ideas into the architects mind which could box them into one way of thinking. Clever ideas could easily be discounted in the minds of your team if you don’t encourage creativity.

Who’s responsible?

When mistake happen (and it is guaranteed they will happen), companies may try to find the culprit and lay the blame on an individual. I’m not interested in finding the scapegoat.

Some of Sony’s major failures in the past included Chromatron, L-cassette and even Betamax. But they also had huge successes with things like the Walkman and more recently, the Playstation. Naturally since this book was written in 1986 there was no Playstation in sight and even at that stage, working with Nintendo on the SPC700 sound system for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System was still a little while away!

“If a person who makes a mistake is branded and kicked off the seniority promotion escalator, he could lose his motivation for the rest of his business life and deprive the company of whatever good things he may have to offer later.”

Morita’s rule is basically mistakes will be made but instead of worrying about who caused them, instead learn from them, and don’t make the same mistake twice.

It’s also very easy to make mistakes in business - so much so that many mistakes go unnoticed. Morita recalls a comparison of someone who is a virtuoso instrumentalist or an amazing artist, who can easily be caught out if they make a mistake. Whereas it’s much easier to ‘hide’ mistakes in business to the point where management could be making mistakes for years without anyone being aware of this.

Morita describes a performance measurement technique for managers in how they extract the most out of the staff they manage: high enthusiasms, willingness to contribute and attracting a large number of people who are all keen on making the organisation a success. This makes a lot more sense to me than measuring on sales or metrics which are highly seasonal or impacted by many other external factors, although I’d rather a combination of multiple metrics rather than a single “harmony” metric.

American vs Japanese system

Morita makes a lot of comparisons between Japan and America in his autobiography, so I won’t repeat them all here, but one thing that stood out to him was the power of the American manager.

He rarely fired anyone from Sony but found that the easiest way to deal with a troublesome employee in their American company was simply to fire the individual, which would not have been an option in Japan.

Problem solved?

Well, conversely, a manager had toured the world and done many great things for Sony and decided it was time to leave for another company, which was offering a lot more money for the same role. So that was an easy choice for that employee to leave.

So it seems there is a double-edged sword from both perspectives of the organisation and the employee who wish to invoke swift change.

Morita also goes into details about how one system is not necessarily appropriate for all locations. It seems like the American arm of the company is run a little differently with less focus on the “family” aspects than the Japanese part. This makes a lot of sense to me because you do need to adapt the model based on the location and the local cultural norms.

A lot of Sony was “Americanised” in the 70’s to lead up to things like the Betamax launch (OK, not their finest hour which was soon to be dominated by VHS in one of many format wars) and it was successful in establishing a solid local presence for the American market.

Profit was the focus for Sony America (also known as “Sonam”) which was also quite different from the demands of Japanese shareholders, who were more interested in long-term growth and appreciation. R&D alone made up 6% of sales and I think this makes a lot of sense for a predominantly product-focused company. For a company without sales (such as a government agency, R&D could be measured based on a % of government funding, grants and minor revenue. The challenge would be to justify such a large spend on activity which may or may not pay off.

Beware being dominated by today’s sales

(or how to stifle innovation)

Morita goes into details about planning for the future and always thinking about the next product, which is an expensive activity.

It’s made even more expensive by the fact that sometimes you need to make popular products (which are turning excellent profits) obsolete. These products have already spent all the R&D, training and development costs and so they are in the highly profitable part of the product lifecycle. But without consideration of change, you could easy neglect new opportunities.

“If you are nothing but profit-concious, you cannot see the opportunities ahead.”

This feels like a bit of an art, but at what moment would you start to draw funds away from something that is successful (this approach seems like it would attract much resistance from an executive board) and then into a new idea, hoping that the new idea doesn’t fall flat?

The key concern of chasing today’s profits, from Morita, is being too led by salespeople and then becoming unable to compete in the market.

Motivating people to be creative

I like creative pursuits in a career. In my mind, architecture is creative, so is coding and so is being a leader. Most things are creative, if you think about it. But I also like the idea that there is a certain freedom in idea generation and thinking about what might be possible. This is what motivates me: the freedom to think of new concepts or approaches which need to be tested. If I wasn’t so free to think of new ideas in an environment of psychological safety, then I don’t think I would be nearly as motivated.

Strikingly, Morita’s approach isn’t what i had expected:

“My solution to the problem of unleashing creativity is always to set up a target.”

Morita talks about a key example which ‘unleashed’ creativity in the US: Sputnik. Or at least, because the Soviet Union launched Sputnik as well as sending the first human into space, there was such a shock for the US that President Kennedy had to set a 10 year target and inspire so many technological solutions in order to participate in the space race.

Amusingly, Morita talks about a ‘young’ Sony researcher who ‘recently’ came up with a new type of display: plasma. He talks about the future where flat TV monitors might be possible. This employee ended up becoming independent from Sony, but it’s funny looking back to see that we really did get to flat TV monitors using plasma technology - even if they weren’t really that good, ran hot and used up a truck load of electricity.

Morita finishes the chapter with referring to the “Sony system” as a way of supporting the original idea creator right from generation through to supporting a product all whilst paying attention to the “family spirit”. The spirit must be weaved throughout the entire lifecycle of the product, which reinforces the need for everyone in the family to contribute to the welfare of every other family member.

Wrapping up

I’m interested, at least in in part, to understand where Sony is today as compared to 1986, but only to the point to see how much they have changed. How much the vision of the leader really matters and what happens when the leader is no longer in control of the company? Does it succeed? Does it go in a new direction? What matters more right now, however, is adapting the learnings from Morita to our own situations and I think there is already lots to consider.

I hope you’ve enjoyed my notes and analysis of Chapter 4 “On Management (It’s all in the family)” from Made in Japan: Akio Morita and Sony. And if you want to read more (in far more detail than I can possibly go into), I would suggest picking up a copy of the book for yourself. A used copy goes for about $20 AUD including shipping, which I think is a great deal. If you do put an order in, I just hope it’s packed carefully!

Like this post? Subscribe to my RSS Feed or

Comments are closed